In my last posting I said

that I would present a case study using what I originally called the Ultimate

Improvement Cycle (UIC) but is now referred to as TLS. This case study involves a company that had been manufacturing truck bodies for the

transportation industry since 1958 and had been one of the recognized industry

leaders. The company had a staff of 17

full time Engineers and Engineering performance was measured by the number of

hours of backlog waiting to pass through Engineering, which seemed odd to me

that such a negative performance metric was being used. I had been hired in as the VP of Quality and

Continuous Improvement because the company was losing market share as well as

delivery dates being missed. In

addition, morale within Engineering was apparently at an all time low. Upon arriving at this company I was informed

that I was also to have responsibility for Engineering. Because of the poor performance in

Engineering, the company had fired their VP of Engineering and I was the

“lucky” recipient of this group.

Apparently the backlog of quotes had risen from their normal 300 hours

to approximately 1400 hours just in the previous 2 months.

My

first step was to create a high-level P-Map and a VSM to better

understand what was happening. I was in

search of the constraint or that part of the process that was limiting

throughput. It was clear immediately

that the constraint was the order entry system in that the process to receive a

request for a quote and deliver it back to the customers was consuming 40

days! And since it only took 2 weeks to

produce and mount the truck body, it was clear to me why market share was

declining. I then created a lower level

P-Map of the quoting process to better understand what was consuming so much

time.

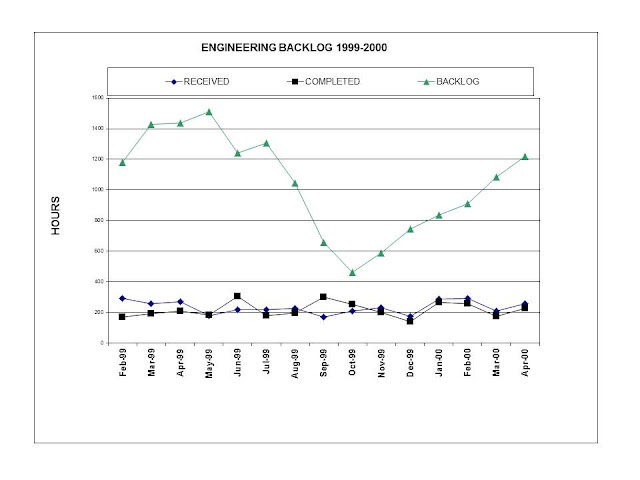

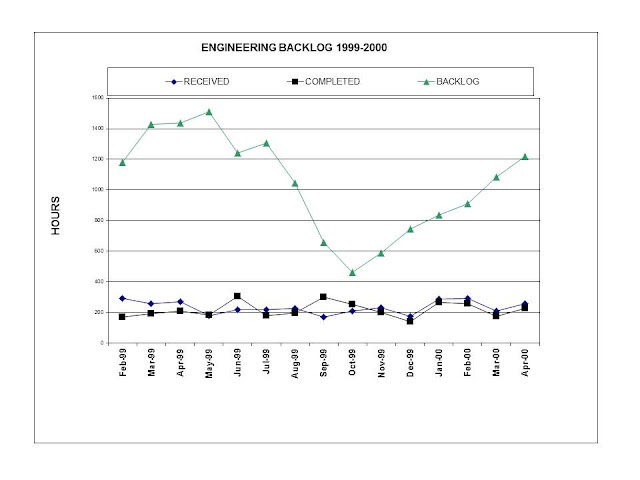

My next step was to develop a

run chart to get some history of what was happening within this process. Figure 1 represents the number of backlog

hours from February 1999 through April 2000.

The data confused me because I first observed a steady decline in

backlog hours beginning in May of 1999 through October 1999 and then a linear

increase from November 1999 through April of 2000. My investigation revealed that the decline

was associated with mandatory Engineering overtime and the ascent occurred when

the overtime was canceled. The

Engineering VP hadn’t defined and solved the problem, he had just treated the

symptoms with overtime.

My next step was to create

another run chart going back further in time.

If I was going to solve this problem, I needed to find out when this problem

actually started. Figure 2 is the second

run chart I created and it was clear that this backlog problem was a relatively

recent change, so the key to solving it was to determine what had changed. Figure

1

Figure

1

In fact, somewhere around

January of 1999 the incumbent VP of Engineering had decided to move on to

another position outside the company.

His replacement apparently didn’t like the way the Engineering Group was

arranged. The company produced three

basic types of truck bodies and historically had three different groups of

engineers to support each type. These

groups were staffed based upon the ratio of each type of truck body ordered and

produced. Between June of 1996 and

December 1998 the company had maintained a very stable level of backlog

hours. The new VP of Engineering

consolidated the three groups into a single group and almost immediately the

backlog grew exponentially. The company

fired him in May 1999 and hired the new VP that used overtime to bring the

backlog hours down. Part of the problem

was the performance metric in place which caused abnormal and unacceptable

behaviors. Figure

1

Figure

1

For me, the fix was

clear. Return to the previous

Engineering configuration, identify the system constraint, focus on it and

drive out waste and variation, to drive the backlog hours lower. The results were swift and amazing in that

the backlog decreased from 1200 hours

to 131 hours in 5 weeks and has remained within an acceptable maintenance level

ever since. In fact, because we also

eliminated much of the waste within this process the time required to process

orders through Engineering decreased from 40 days to an astounding 48 hours! Figure 3 represents the final results of our

efforts. Not only had the amount of

backlog hours decreased to levels never seen before (from a historical average

of 300 hours to less than 150 hours), the number of quotes completed were at

all-time highs for the company.

Figure

3

Figure

3

The key to this success was

to first identify the operation that was constraining throughput (the system

constraint), second, decide how to exploit the constraint by applying various Lean

and Six Sigma tools to the constraint, third, subordinate everything else to

the constraint and then if need be, break the constraint by spending

money. Thanks to Lean and Six Sigma, we

did not have to spend any money. And the

good news is, Engineering overtime was virtually eliminated while the market

share rose to unprecedented levels!

Bob Sproull

No comments:

Post a Comment