Continuing with my series on excerpts from The Ultimate Improvement Cycle, in this posting we will look

at the Theory of Constraints and its shortcomings and benefits and then begin

to tie these three improvement benefits together. The question becomes, should these

methodologies have to exist in isolation from each other or should they be

considered together? One point I didn't mention about Six Sigma implementations is the length of time it takes to complete a project which is at least 3 months. For me, this is a limiting factor because companies today are looking for rapid improvement and 3-5 months in many cases is simply too long.

The Drawbacks of TOC

And what about Theory of

Constraints (TOC)? Has it failed as well? Eli Goldratt, author of The

Goal, believed that organizations

could not maximize profitability unless they maximized their throughput through

the exploitation of the system’s weakest link. But like Six Sigma and Lean

manufacturing, for many companies TOC has not delivered the huge rewards

predicted by Goldratt. Some believe that the reason for this failure is

strictly a question of poor planning and execution. Still others believe that TOC is not an

improvement initiative at all. Theoretically,

the implications of TOC to improvement initiatives can be profound. From a

throughput accounting perspective, reduction in inventory (one of the benefits

of Lean) has a functional lower limit of zero, and once you have reached zero

inventory, there is none left to harvest. Lowering inventory can lead to

substantial dollars, but it is a one-time occurrence. Operating expense reduction,

the favorite of many Lean and Six Sigma aficionados, also has a functional lower

limit, but when this lower limit is surpassed, further attempts to reduce it

can actually debilitate an organization.

Throughput improvement, on the

other hand, has no upper limit. Even if the productive capacity of the

organization exceeds the number of customer orders, the market becomes the

constraint, so lead time and cost reductions can be used to generate more

sales. It is important to remember that if you have excess capacity, as long as

your new product cost covers your cost of raw materials and you have not added

excess labor to achieve this excess capacity, the net flows directly to the

bottom line. Of course, all three of these actions (throughput increases, inventory

reductions, and operating expense reduction) have a positive impact on net

profit and return on investment. Think about this: If there were no constraints

in a company, wouldn’t their profits be infinite?

What TOC Is

The Theory of Constraint’s

process of ongoing improvement is a direct result of always focusing your

efforts toward achieving the system’s goal. In order to achieve this focus,

Goldratt developed a five-step process toward that end:

- Identify the system’s constraint(s).

- Decide how to exploit the system’s constraint(s).

- Subordinate everything else to the above decision.

- Elevate the system’s constraint(s).

- If in the previous steps a

constraint has been broken, go back to step 1, but do not allow inertia to cause a

system constraint.

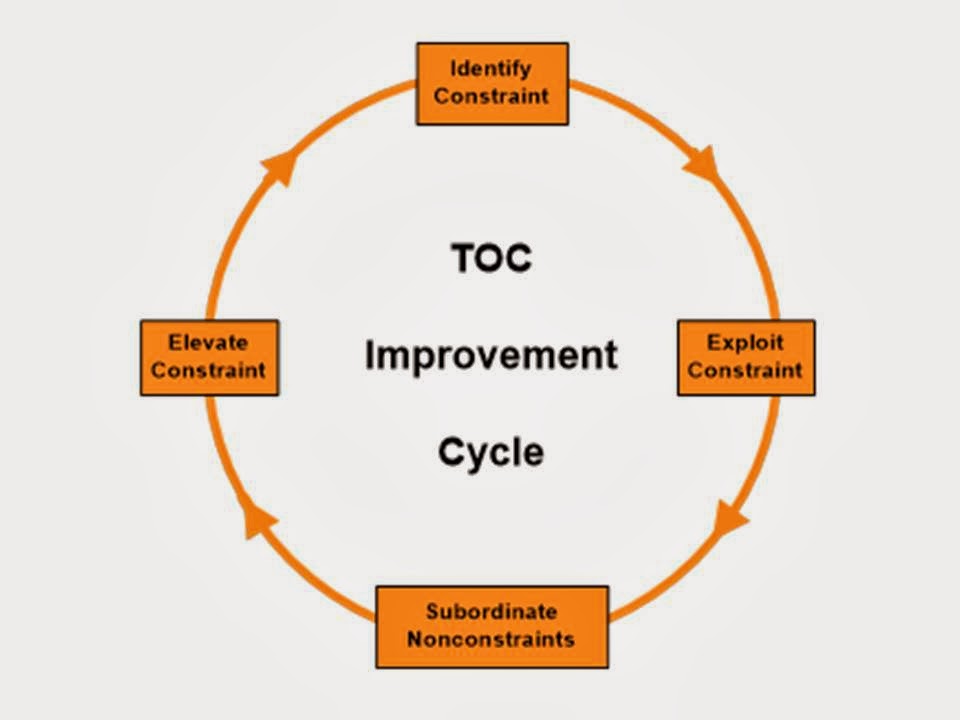

The figure below is a graphic

illustration of the Theory of Constraints improvement cycle, with the four

major steps included. By making this cyclic representation, we automatically

assumes that once a constraint has been elevated, it will be broken and a new

constraint will take its place. Let us look at each of these individual steps

in a bit more detail, with the help of Goldratt and Dettmer.

Identify

the System Constraint(s)

Just as a chain has a weakest

link, there will always be a resource of some kind that limits the system from

maximizing its output. In order to improve the system’s performance, it is

imperative that you locate the weakest organizational link and focus your

improvements there. There is a logistical value chain of mutually supporting processes

and operations in every company or manufacturing facility. Included within this

value chain is the organization’s weakest link that limits the performance of

the total organization. It may not be obvious to you, but when you are looking

for a starting point, in any improvement initiative, it should always be the

system’s constraint simply because it offers the greatest opportunity to

increase profits in a relatively short period of time. Whether your constraint

is a flow problem, a quality problem, a capacity problem, or a policy problem,

it should be identified as the area on which to focus your efforts. This first step answers the

question “What should you change?”

Decide

How to Exploit the System’s Constraint(s)

Once you have identified the

restrictive link in the organizational chain that is limiting throughput, you

must decide how to take advantage of or squeeze the most out of it. For

example, if the constraint is one of the steps in a manufacturing process that

is limiting the output of the entire process (a bottleneck), you must take all

necessary actions to improve the rate at which parts flow through this

bottleneck. If you do not increase the rate through the bottleneck, throughput will

not increase. It is really that simple. By increasing the flow of product through

the constraint, you automatically improve the system throughput, which

translates into more revenue and more bottom-line dollars. This second step

answers the question “What should you change to?”

Subordinate

Everything Else to the Above Decision

This is one of the most important

steps in terms of resource utilization, with “resources” meaning nonconstraint

operations, people, and so on. The nonbottleneck resources should work only at

the same pace as the constraint operation—neither faster nor slower. If the

nonconstraints are permitted to run faster than the constraint, the result is

excess in-process inventory and prolonged cycle times. If they are permitted to

run slower than the constraint, the output of the constraining operation may be

jeopardized, as would the organization’s throughput. This subordination step is where most

companies attempting to embrace and implement TOC have failed. Your

organization must be totally committed to subordinating all other resources to

the constraint operation or you will not realize all the potential throughput

gains (and profits) that you could or should.

This step begins to answer the question “How do you make the change?”

Elevate

the System’s Constraint(s)

If the actions taken in steps 2

and 3 do not break the constraint, you will be forced to take other actions on

the constraint itself. These actions could include using additional shifts,

additional overtime, adding additional resources (e.g., equipment or people),

or as a last resort, radically changing the process through automation or a new

product or process design. Although this step and step 3 answer part of the

question “How do you make the change?” they do not provide enough insight as to

what might be done.

If

in the Previous Steps a Constraint Has Been Broken, Go Back to Step 1, But Do

Not Allow Inertia to Cause a System Constraint

The aim of the first four steps

of TOC is focused on breaking the organizational or system constraint. Once you

have accomplished this, you must now guard against backsliding, which could

result in the constraint becoming a constraint once again. For this reason, you

must always develop some type of control that serves as an alert to guard

against any kind of reversion to old ways.

In my next posting we’ll first

discuss what TOC is not and then discuss

why we need to integrate these methodologies.

Bob Sproull

No comments:

Post a Comment