I want to thank all of my readers and followers of my blog. In January, I thanked everyone for taking the blog to a new all-time high of page views at 25,000 (up from a high of 12,000 in December). In February, we almost doubled that amount by having 47,000. In March, I am very proud to announce that the number of page views has surpassed 94,000 for the month. So for 3 consecutive months, the number of page views has doubled in each successive month. I want to thank everyone so much for such an amazing feat!!

Bob Sproull

My blog is focused primarily on the Theory of Constraints and how to use it to maximize the profitability of any company. I also discuss why integrating TOC with Lean and Six Sigma is the most dynamic improvement methodology available today.

Monday, March 31, 2014

Blog Posting Index through March 31, 2014......

Post # Subject Discussed

As promised, here is an updated posting index through March 31, 2014. Each of the following postings can be reached by

searching for the number designation below.

For example: 1 is Focus and

Leverage or 2 is Focus and Leverage Part 2 and so forth. The link to the first blog posting is: http://www.blogger.com/blogger.g?blogID=4654571158555106378#editor/target=post;postID=4464386559619829406

1. Introduction

to TOC – Lean – Six Sigma

2. Why

Improvement Initiatives Fail

3. The

Basic Concepts of TOC

4. Throughput

Accounting

5. The

Process of On-Going Improvement (POOGI)

6. The

3 Cycles of Improvement

7. Combining

TOC, Lean and Six Sigma Graphically

8. Step

1a Performance Metrics

9. Planning

Steps 1b and 1c Reducing Waste and Variation

10. Developing

a Constraint’s Improvement Plan

11. This

number was skipped

12. Steps

1b and 1c Reducing Waste and Variation plus an intro to DBR

13. Drum-Buffer-Rope

14. The

Final Steps of UIC

15. How

do I start the UIC?

16. The

10 Prerequisite Beliefs

17. Comparing

Lean, Six Sigma and TOC

18. Types

of Constraints

19. The

Logical Thinking Processes

20. Undesirable

Effects (UDE’s)

21. Categories

of Legitimate Reservation

22. Current

Reality Trees

23. Constructing

Current Reality Trees

24. Conflict

Diagrams Basic Principles

25. Constructing

Conflict Diagrams

26. Intro

to Future Reality Trees

27. Constructing

Future Reality Trees

28. Prerequisite

Trees

29. Constructing

Prerequisite Trees

30. Transition

Trees

31. Constructing

Transition Trees

32. Book

Announcement

33. Project

Management Failures

34. Project

Management Negative Behaviors

35. Critical

Path Management (CPM)

36. Critical

Chain Project Management (CCPM)

37. Tracking

Projects In CCPM

38. Final

Posting on CCPM

39. Intro

to the TOC Parts Replenishment Model versus the Min/Max System

40. The

TOC Parts Replenishment Model

41. Interview

with Joe Dager from Business901

42. Deming,

Ohno and Goldratt Commonality

43. Dedication to Dr.

Eliyahu Goldratt

44. How processing time, cycle time, throughput and WIP are

interrelated

45. Little’s Law

46. Batch and queue production system and the fallacy of a balanced

line

47. Why an unbalanced line is better.

48. What prevents me from making more money now and more money in

the future?

49. More on the 10 Prerequisite Beliefs

50. Motivating a work force to actively participate in improvement

initiatives

51. Re-Introducing the Intermediate Objectives Map

52. Introducing Be Fast or Be Gone: Racing the Clock

with CCPM

53. Parkinson’s Law, The Student Syndrome, Cherry Picking and

Multi-Tasking

54. Overcoming the four negative behaviors in Project Management

55. Intro to combining the Interference Diagram

(ID) and the IO Map

56. The Simplified Strategy

57. The Interference Diagram

58. Interference Diagram for Strategy

59. The ID/IO Simplified Strategy

60. Preface Part 1 for Epiphanized©

61. Preface Part 2 for Epiphanized©

62. CHAPTER 1 Part 1 for Epiphanized©

63. CHAPTER 1 Parts 2 and 3 for Epiphanized©

64. CHAPTER 1 Part 4 for Epiphanized©

65. CHAPTER 1 Part 5 for Epiphanized©

66. Focused Operations

Management For Health Service Organizations by Boaz Ronen, Joseph Pliskin and

Shimeon Pass

67. Marketplace Constraints

68. A Discussion on Variability

69. More Discussion on Variability

70. Still More Discussion on Variability

71. Paper from the International Journal of Integrated Care

72. Value Stream Mapping

73. Paths of Variation

74. Step 3, Subordination

75. The Key to Profitability: Making Money Versus Saving Money

76. My

First Experience With TOC

77. TOC in Non-Manufacturing Environments

78. Deborah Smith’s Excellent Chapter in the TOC Handbook (i.e.

Chapter 14)

79. More on Performance Metrics

80. Efficiency, Productivity, and Utilization (EPU) ©

81. Productivity

as a Performance Metric

82. Utilization

as a Performance Metric

83. What the Dog Saw –Malcolm Gladwell

84. Speaking

at the CPI Symposium – Cal State, Northridge

85. NOVACES–

A Great Young Company

86. NOVACES’SystemCPI©

87. Problems

With My Publisher

88. The

Why? – Why? Diagram

89. Experience

With the Integrated Methodology

90. A

New Piping Diagram

91. The

Healthcare Industry

92. More

Bad News From the Publisher

93. A

Message from the CPI Symposium

94. Multiple

Drum-Buffer-Rope

95. Problem

Solving Roadmap

96. Problem

Prevention Roadmap

97. Improving

Profitability

98. More

on Throughput Accounting

99. More

on Parts Replenishment

100. TLS

101. Engaging the "Money Makers" in Your Company

102. A Conversation on the Theory of Constraints

103. The Key to Successful Consulting Engagements

104. The Three Basic Questions to Answer

105. A Problem With the Airlines

106. A Better Way to Improve Processes and Systems

107. The Problem With Project Management

108. Critical Path Project Management Revisited

109. Critical Chain Project Management Revisited

110. The

Fever Chart

111. Comparing

CPM and CCPM

112. Performance

Improvement for Healthcare – Leading Change with Lean, Six Sigma and Constraints

Management

113. More on Performance

Improvement for Healthcare

114. Even more on Performance

Improvement for Healthcare

115. Still One More on Performance

Improvement for Healthcare

116. The Final One on Performance

Improvement for Healthcare

117. The Real Final One on Performance

Improvement for Healthcare

118. Focused Operation's

Management for Health Services Organizations.

119. Focused Management Methodology

120. The Clogged Drain

121. The “Soft” Tools of Improvement

122. More on TOC’s Distribution/Replenishment solution

123. Still

More on TOC’s Distribution/Replenishment solution

124. Amir Schragenheim’s Chapter 11 entry in the TOC Handbook

125. Comparison of Lean, Six Sigma and TOC

126. A Simple Lesson on Applying TLS to Your Processes

127. A Historical Index of Blog Postings

128. Mafia Offer Part 1

129. Mafia Offer Part 2

130. Mafia Offer Part 3

131. Airline Problems

132. A YouTube Interview with Bob Sproull and

Mike Hannan

133. Active Listening

134. Viable Vision

135. Throughput Accounting

136.

Performance Metrics

137.

On-the-Line Charting

138.

Comment on Epiphanized from a

reader in the US Marines

139.

Active Listening

140.

Healthcare Case Study

141. Change

142.

Getting buy-in for Change

143.

Aviation Maintenance, Repair and Overhaul Client Part 1

144. Aviation

Maintenance, Repair and Overhaul Client Part 2

145.

Continuous Improvement in Healthcare

146. Using

Your Senses in Continuous Improvement

147. A

Video by Phillip Marris on CI

148. An

article about a Construction Company Using the TOC Thinking Processes

149. Using

TOC in Healthcare Part 1

150. Using

TOC in Healthcare Part 2

151. Using

TOC in Healthcare Part 3 Supply Replenishment

152. Using

TOC in Healthcare Part 4 Supply Replenishment (con’t)

153. Using

TOC in Healthcare Part 5 Supply Replenishment (final)

154. The

Sock Maker

155. The

Negative Effects of Using Efficiency

156. Cost

Accounting Part 1

157. A

Political Voting Story

158. Cost

Accounting Part 2

159. Cost

Accounting Part 3

160. Using

TLS for the Affordable Care Act

161. The

System Constraint in Hospitals Part 1

162. Wait

Times in Hospitals

163. The

Oncology Clinic Case Study Part 1

164. The

Oncology Clinic Case Study Part 2

165. Article:

Emergency Department Throughput, Crowding, and Financial Outcomes for Hospitals

166.

Goldratt’s 5 Focusing Steps in Healthcare

167. My

First Experience With TOC Part 1

168. My

First Experience With TOC Part 2

169. My

First Experience With TOC Part 3

170. My

First Experience With TOC Part 4

171. My

First Experience With TOC Part 5

172. My

First Experience With TOC Part 6

173. Healthcare

Case Study Part 1

174.

Healthcare Case Study Part 2

175.

Healthcare Case Study Part 3

176. TOC

in Healthcare

177.

Healthcare Case Study Part 4

178. My

Transition From Aviation Maintenance to Healthcare

179. Door

to Doc Time Case Study Part 1

180. Door

to Doc Time Case Study Part 2

181. Door

to Doc Time Case Study Part 3

182. Door

to Doc Time Case Study Part 4

183. My

White Paper in Quality Forum Part 1

184. My

White Paper in Quality Forum Part 2

185. My

White Paper in Quality Forum Part 3

186. A

Meeting on Epiphanized at the

Pittsburgh Airport

187.

Billing for Immunizations Case Study Part 1

188. Some

Thoughts on Performance Improvement Part 1

189. Some

Thoughts on Performance Improvement Part 2

190. Case

Study on Using TOC in Healthcare

191. IO

Map

192. TOC

Thinking Process Tools Part 1

192B. TOC

Thinking Process Tools Part 2

193. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 1

194. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 2

195. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 3

196.

Synchronized and Non-synchronized Production

197.

Competitive Edge Factors

198. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 4

199. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 5

200. Case Study

on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 6

201. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 7

202. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 8

203. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 9

204. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 10

205. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 11

206. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 12

207. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 13

208. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 14

209. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 15

210. Case

Study on How to Use TOC’s Thinking Processes Part 16

211. The

IO Map Revisited Part 1

212. The

IO Map Revisited Part 2

213. The IO

Map Revisited Part 3

214. The

IO Map Revisited Part 4

215. An

Interview About The Ultimate Improvement

Cycle by Joe Dager

216. Healthcare

Case Study: Door to Balloon Time Part 1

217. More

On My First Experience With TOC Part 1

218. More

On My First Experience With TOC Part 2

219. More

On My First Experience With TOC Part 3

220. More

On My First Experience With TOC Part 3

221. More

On My First Experience With TOC Part 4

222. A

Discussion on Constraints Management Part 1

223. A

Discussion on Constraints Management Part 2

224. A

Discussion on Constraints Management Part 3

225. A

Discussion on Constraints Management Part 4

226. A

Discussion on Constraints Management Part 6

227. How I

Present TOC Basics to Students & Teams Part 1 (Most viewed of all posts)

228. How I

Present TOC Basics to Students & Teams Part 2

229.

YouTube Video on Improving Flow Through a Bottleneck

230.

YouTube Video on Throughput Accounting

231.

YouTube Video on What to Change

232.

YouTube Video on What to Change To

233.

YouTube Video on How to Cause the Change to Happen

234. A

Meeting With an Executive of a Larger Corporation

235. The

Missing Link

236. You

Tube Video by Goldratt on Henry Ford and Taichi Ohno

237. Prevention

Versus Detection – The Bug Guy

238. An

Article by Anna Gorman of the LA Times

239. TOC’s Solution to Supply Chain Problems

240. The Nun

and the Bureaucrat Part 1

241. The Nun

and the Bureaucrat Part 2

242. The Nun

and the Bureaucrat Part 3

243. The Nun

and the Bureaucrat Part 4

244. The Nun

and the Bureaucrat Part 5

245. The Nun

and the Bureaucrat Part 6

246. A Healthcare Clinic Case Study Part 1

246B. An Update to Focus and Leverage Part 246

247, Drum Buffer Rope in Manufacturing

248. The Sock Maker Revisited Part 1

249. The Sock Maker Revisited Part 2

250. Throughput Accounting Part 1

251. Throughput Accounting Part 2

252. Throughput Accounting Part 3

253. How to Use and Integrated TOC, Lean & Six

Sigma Methodology Part 1

254. How to Use and Integrated TOC, Lean & Six

Sigma Methodology Part 2

255. How to Use and Integrated TOC, Lean & Six

Sigma Methodology Part 3

256. How to Use and Integrated TOC, Lean & Six

Sigma Methodology Part 4

257. How to Use and Integrated TOC, Lean & Six

Sigma Methodology Part 5

258. Critical Path Project Management Versus

Critical Chain PM Part 1

259. Critical Path Project Management Versus

Critical Chain PM Part 2

260. Critical Path Project Management Versus

Critical Chain PM Part 3

261. Critical Path Project Management Versus

Critical Chain PM Part 4

262. Critical Path Project Management Versus

Critical Chain PM Part 5

263. Critical Path Project Management Versus

Critical Chain PM Part 6

264. The Cabinet Maker – A TOC Case Study Part 1

265. The Cabinet Maker – A TOC Case Study Part 2

266. The Cabinet Maker – A TOC Case Study Part 3

267. The Cabinet Maker – A TOC Case Study Part 4

268. How I Run Improvement Events

269. Using The Goal Tree vs. the Full Thinking

Process Analysis Part 1

270. Using The Goal Tree vs. the Full Thinking

Process Analysis Part 2

271. Using The Goal Tree vs. the Full Thinking

Process Analysis Part 3

272. Using The Goal Tree vs. the Full Thinking

Process Analysis Part 4

273. Using The Goal Tree vs. the Full Thinking

Process Analysis Part 5

274. Using The Goal Tree vs. the Full Thinking

Process Analysis Part 6

275. An Analysis of Focus and Leverage’s Top Page

View Postings

276. An Index of All Focus and Leverage Blog Posts

277. Using the Thinking Processes in Healthcare

Part 1

278. Using the Thinking Processes in Healthcare

Part 2

279. Using the Thinking Processes in Healthcare

Part 3

280. The Four Disciplines of Execution Part 1

281. The Four Disciplines of Execution Part 2

282. The Four Disciplines of Execution Part 3

283. The Four Disciplines of Execution Part 4

284. The Four Disciplines of Execution Part 5

285. The Goal Tree – A New Way to Make it and Use

It Part 1

286. The Goal Tree – A New Way to Make it and Use

It Part 2

287. The Goal Tree – A New Way to Make it and Use

It Part 3

288. Operation Excellence by Jim Covington

289. The Saw Mill Assessment

290. How I present the Theory of Constraints to

People Not Familiar With it

291. David and Goliath – Malcolm Gladwell’s Latest

Book

292. The Basics of TOC

293. TOC’s Replenishment Model Part 1

294. TOC’s Replenishment Model Part 2

295. Blog Posting Index

296. Overcoming Natural Resistance to Change

297. Integrating TOC, Lean and Six Sigma Part 1

298. Appendix 1 from Epiphanized Part 1

299. The Winter Storm in Atlanta

300. Appendix 1 from Epiphanized Part 2

301. Appendix 1 from Epiphanized Part 3

302. Appendix 1 from Epiphanized Part 4 Final

303. Bill Dettmer videos on TOC’s Thinking

Processes

304. Queuing Theory Part 1

305. Queuing Theory Part 2

306. Delta Airlines Lack of Customer Focus

307. Bill Dettmer’s Book Strategic Navigation

308. Excerpts from The Ultimate Improvement Cycle – My second book Part 1

309. Excerpts from The Ultimate Improvement Cycle – My second book Part 2

310. Excerpts from The Ultimate Improvement Cycle – My second book Part 3

311. Excerpts from The Ultimate Improvement Cycle – My second book Part 4

312. Excerpts from The Ultimate Improvement Cycle – My second book Part 5

313. The

Ultimate Improvement Cycle – Step 1:

Identify - My second book Part 6

314. The

Ultimate Improvement Cycle – Step 2:

Define, Measure and Analyze - My second book Part 7

315. The

Ultimate Improvement Cycle – Step 3:

Improve - My second book Part 8

316. The

Ultimate Improvement Cycle – Step 3:

Control - My second book Part 9

317. Throughput Accounting Part 1

318. Throughput Accounting Part 2

319. Throughput Accounting Part 3

320. Throughput Accounting Part 4

321. Throughput Accounting Part 5

322. Throughput Accounting Part 6

323. Throughput Accounting Part 7 Final

324. Optimium Health’s Amazing New Software for

Healthcare

325. Personal experiences using Throughput

Accounting

326. MRO Project Management Case Study Part 1

327. MRO Project Management Case Study Part 2

328. MRO Project Management Case Study Part 3

329. MRO Project Management Case Study Part 4

330. MRO Project Management Case Study Part 5

Focus and Leverage Part 330

In this posting we’ll take a look

at the stark differences between CCPM and CPM and why I believe that CCPM is

the superior method. If you have any comments or questions, please leave them in the comments section of this blog and I will respond to them.

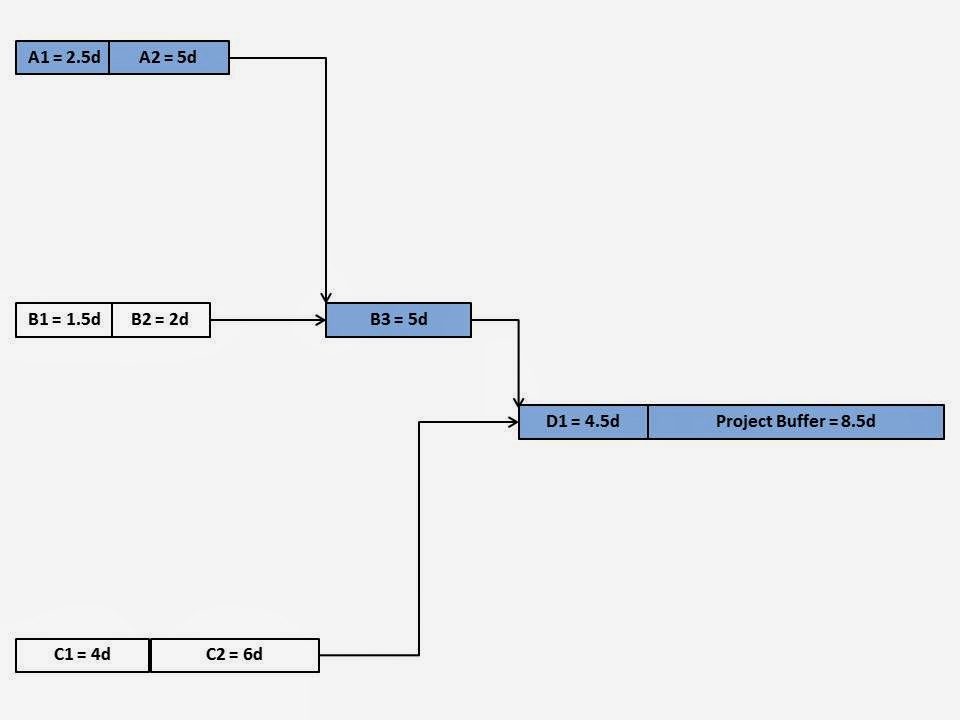

In CPM, tasks are over-inflated by at least 50 percent and here’s where we take advantage of this extra time. We now subtract half of the time estimates from each one of the tasks and create a project buffer as in the following figure.

In CPM, tasks are over-inflated by at least 50 percent and here’s where we take advantage of this extra time. We now subtract half of the time estimates from each one of the tasks and create a project buffer as in the following figure.

As you can see, the new

tasks times are half of the original estimates, but you can also see that we

now have added a project buffer. The

project buffer becomes half of the time we have taken from the task

durations. The next question we now posed to leadership

was, how does having this project buffer improve the on-time completion of projects? Surprisingly, one member of the leadership

team was able to give a wonderful analogy to answer this question. The team member said, “If I understand this

concept, then the project buffer works just like a bank account with deposits

and withdrawals. If a task takes longer

than the estimate, you withdraw time from the project buffer, but if the task

is finished in a shorter amount of time, you add the time back into the project

buffer. We told him this was a great

analogy.

With CPM, delays are

passed on while gains are lost and this is such a significant difference! The project buffer protects the project from

delays. We also explained that we also

add feeding buffers to make sure that tasks not on the critical chain are

completed on time.

At this point there was a

question from the leadership team on why we thought that having this project

buffer would eliminate the Student Syndrome and Parkinson’s Law and we answered

this question in the following way. In

traditional project management, that is using the Critical Path Method (CPM),

each task has a scheduled start and finish date. CCPM completely removes the start and finish

dates from the schedule so that the focus will be passing on tasks as soon as they

are completed. In doing so, both the Student Syndrome and Parkinson’s Law are

pretty much neutralized. We explained that CCPM uses a relay race mentality

whereby the runner completes a certain distance and then passes off the baton

to the next runner who is waiting.

Earlier I explained that in CPM

we track progress of the project by calculating the percentage of individual

tasks completed and then comparing that percentage against the project due date.

The problem with this method is that it

is nearly impossible to know how much time is remaining to complete the project.

If you use this method to track

progress, many times you’ll see 90 percent of a project completed only to see

the remaining 10 percent take just as long. In fact, looking at the number or

percentage of tasks completed, instead of how much of the critical path has

been completed, only really serves to give a false sense of schedule conformance. CCPM measures project performance in a much

different way, and in so doing, allows the project to make valuable use of

early finishes of tasks. CCPM uses something called a Fever Chart, which is

simply a run chart of the percentage of the critical chain completed versus the

percentage of project buffer consumed. In the figure below, you’ll see three different

colored zones. We explained the

different colors as follows: Green means

that the project is progressing either on or ahead of schedule; yellow means

that the project is using more buffer than progress is being made and that it’s

time to develop a plan to reduce the rate of buffer consumption. Red means that buffer is being used at an

alarming rate and that if no action is taken, the project will definitely be

late.

In order to reinforce the

interpretation of this color scheme, we then asked the leadership team if it

was ever acceptable for your project to finish the project in the red on the

fever chart and virtually everyone said no, except for one person. We then asked, this person to explain under

what circumstances that it would that be acceptable.

The response was that ss long as

the critical chain is 100 percent completed, and you haven’t used more than 100

percent of your project buffer, then finishing in the red is perfectly

acceptable. We agreed and told them that

in fact, if both of these variables are at the 100 percent level, the project

is exactly on time.

It was very important that

the leadership team understood how to interpret the fever chart, so we then

asked for a volunteer to explain what they saw on this fever chart. Some did volunteer and explained it very

well. Tis project started off ahead of

schedule by completing 20 percent of the critical chain while only consuming 8

percent of the buffer. But if you look at the latest data point, only 41

percent of the chain is complete, but 72 percent of the buffer has been consumed,

This project is now behind schedule, and unless some kind of intervention is

undertaken, this project will be late.

It doesn’t mean that this project is doomed to be late, but rather it

only means that some kind of action must be taken, or the project will be late

completing.

The key point to remember

here is that you should get excited with vertical rises because it always

spells trouble if left unattended, In

addition, we explained that if you divide the percent of the critical chain

completed into the percent of buffer consumed, this ratio could give a single

number that would tell you how well you’re doing. So if your ratio was above one, your rate of

buffer consumption would be too high, while if the ratio is below one, everything

is going well. This was important for

the leadership to understand because they would not have to review every fever

chart for every project. They could

simply look at the ratio for each project and know if it was on schedule or whether

it might need their help.

One other point we presented to the

leadership team was the concept of a portfolio of projects. We presented the fever chart above to let

them know that this was a tool that would allow them to see, at a glance, which

projects might need their attention. On

a single sheet of paper or one computer screen, they would be able to see which

projects were red and yellow….those that might need their attention and which

projects that they could ignore (i.e. the green ones). In the above fever chart we asked them which

ones might be in need of an intervention and they all rightfully told us that

projects 1 and 7 were clearly eating up buffer at an unacceptable rate and that

projects 2, 3 and possible 8, might need some work. They also recognized that projects 4, 5, 6

and 9 did not pose a threat, at least for the moment.

There was another side of

the CCPM implementation that we explained to the leadership team, key things

that must be done if their CCPM implementation was going to be successful. We

explained that every day there must be stand-up meetings with the key resources

to find out what their resources might need.. By that we meant that they should

go to the resources and ask them if they have everything they need and if they

have any problems. The leadership team needed to understand that if the “boots

on the ground” executing the projects couldn’t resolve their issues, then they

must escalate the problem up through the various levels of management. We explained that although this may sound

trivial, it truly isn’t and that if this step is not taken seriously, the

implementation will never be sustained.

In my next posting, we’ll take a look at the

results achieved as a result of this implementation.

Bob Sproull

Saturday, March 29, 2014

Focus and Leverage Part 329

In this posting, I’m going

to discuss how we explained a new form of Project Management known as Critical

Chain Project Management (CCPM) and how we were able to differentiate it from

the Critical Path Method (CPM). We’ll

also discuss how the results of this new method significantly impacted the

completion rates of projects and delve into the financial impact of this

implementation.

As a refresher, we said

that CPM task durations are inflated to protect against Murphy, but what if

there was a way to significantly reduce these imbedded safety buffers and

still be able to provide the protection from Murphy that we need? Using my example from Part 328, suppose we

were able to reduce the estimated duration by as much as 50 fifty percent and

still protect against Murphy. Does that sound like a significant

reduction? You may be thinking that, if

this contractor was already late on projects with all of this built-in safety,

how in the world would reducing these durations result in better project on-time

completion rates? What I’m proposing is

that on my example from Part 328, we said that we had three projects each with

an estimated duration of nine days. Referring to the drawing below, using CCPM,

I’m suggesting that each project will now take only four and a half days and

the total time to complete all three projects would theoretically be thirteen

and a half days.

It was a daunting task to

convince this contractor’s leadership that we could reduce their imbedded

safety by a factor of 50 percent and still safely guard against the uncertainty

introduced by Murphy. In order to

convince the contractor that this was indeed possible, I found it necessary to refresh

their minds a bit on the Theory of Constraints. Specifically, I presented the piping diagram

and the simple four-step process that I presented to them during their initial

training on TOC. For you first timers to

my blog, the figures below are what I am referring to here.

Our CI Team asked the leadership

team to tell us what was the key to improving throughput in both of those

drawings and they correctly stated that they would have to identify the

constraint and then exploit it. We also

asked them to tell us how they would prevent a WIP explosion in the process,

and they correctly told us that it would be necessary to subordinate everything

else to the constraint. We then asked

them whether or not reducing cycle times at non-constraints was a fruitless

exercise to which they told us that they should only focus on the system constraint

and that it should never be idle. This was very important for them to

understand because of how CCPM works. In

other words, we wanted the existence of a constraint to be foremost in their

minds as we moved on.

Next, we asked leadership to tell us what the

constraint was in their maintenance projects.

After careful deliberation, only one person raised their hand and explained

that in a project, it’s not the longest task necessarily that is the

constraint, but it’s probably the longest set of sequential tasks, where one

task is dependent upon another and that this series of interconnected tasks

is probably the constraint. This was a

correct answer, so we explained that this series of dependent tasks is actually

referred to as the critical path which in CPM is, in fact, the constraint. We needed them to understand this concept so

that when we presented the concept of CCPM, they would see that it too is the

constraint, but that it’s very different than CPM’s Critical Path.

In Focus and Leverage Part 328, I presented

two behaviors known as the Student Syndrome and Parkinson’s Law and how both of these behaviors work to extend the time required to

complete a project. I explained that with

CPM, planning resources estimate individual task times and then add in their

own protection against disruptions caused primarily by Murphy. And then the

effects of Parkinson’s and the Student Syndrome waste most of the safety that

has been added. So the question our implementation

team had to explain was, how does CCPM deal with these behaviors?

We explained that while CPM

relies on individual task durations as well as scheduled start and finish

dates, CCPM does not. The project focus

is no longer on finishing individual tasks on time, but rather completing tasks

as soon as possible. Like CPM, CCPM

still gathers estimates on individual tasks and identifies its own version of

the critical path that is referred to as the Critical Chain. However, unlike

CPM, CCPM also considers the competing resources and includes them as part of

the critical chain. We then presented an example of this new way of looking at

projects as depicted in the following figure.

As I explained earlier,

CPM defines the critical path as the longest path of dependent tasks within a

project. That is, tasks are dependent when the completion of one task isn’t

possible until the completion of a preceding task. Any delay on the critical path will delay the

project correspondingly. In this figure,

the critical path is highlighted according to the CPM method. It’s important to remember that CPM

determines the critical path by looking at the task dependencies within the project. So using CPM, the critical path would be

C1-C2-D1, and the project completion estimate would be the sum of those days,

or twenty-nine days. We wanted to draw a

distinction between CPM and CCPM, so it was important for the contractor’s

leadership to understand their existing methodology.

One of the shortcomings of CPM is

the failure to consider or recognize the existence of resource dependencies, so

what if, in our example in the above figure, tasks A2 and B3 are performed by

the same resource? Would the critical path be different? Since A2 and B3 are done by the same

resource, they can’t both be done at the same time. Because of this dependency,

we have to move B3 to begin after the same resource completed A2. So the new critical path would be A1-A2-B3-D1

and the new project estimate increases from the original twenty-nine days to

thirty-four days as seen in the figure below.

So the question now

becomes, what does the recognition of resource dependencies do to the on-time

completion of this project? It means

that without considering resource dependencies, using CPM, the project is

guaranteed to be late! This simple

consequence of incorrectly identifying the critical path—which we now refer to

as the critical chain—is that the project team will never be able to complete

their project on time without heroic efforts, adding additional resources,

overtime or a combination of all three. In presenting these project drawings,

it was now evident to the contractors leadership that the practical implication

of incorrectly identifying the real critical chain is that the focus will be on

the wrong tasks which is really no different than focusing on non-constraints

in a production process, right? This

explanation made it easy to see why the contractor’s projects are late so

often.

One of the leaders then

said that "There seems to be a problem that when we add resource dependencies to

the project, it will actually lengthen the project completion time, and that’s

not what we want…..we want to shorten them."

We then asked leadership what they thought we had to do to shorten the project

time? None of them had an answer. Remember earlier how we said that excessive

safety is imbedded within each task as a way to guard against the uncertainties

of Murphy? CCPM takes a completely

different approach by assuming that Murphy’s uncertainty will happen in every

project and unlike CPM, CCPM actually removes these safeties within each task

and pools them at the end of the project to protect the only date that really

matters, the project completion date. In

other words, instead of protecting the task due dates, we shift our thinking to

protecting the project due date and there is a significant difference.

In my next posting we'll dive deep into Critical Chain Project Management (CCPM) and discuss why it is so superior to the Critical Path Method (CPM).

Bob Sproull

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)