Maximizing

Profits Through the Integration of Lean, Six Sigma and TOC

By Bob

Sproull

I

must say that I’ve been very fortunate in my career. Not because I have been successful

financially, although I haven’t done badly.

I’ve been fortunate because I’ve been able to be a part of so many

different improvement initiatives over the years. I was around during the Deming years and was

able to learn and apply his now famous 15 principles as well as his teachings

regarding the significant impact variation has on processes and systems. I was around when Lean and Six Sigma came

upon the scene and was fortunate enough to have worked for a great TPS

consulting firm. All of these and more

had a very profound impact on me as a professional.

Like

most consultants I was looking to remove waste and variation in every process I

touched. After all, waste and variation

exists everywhere right? If I could

reduce both of these harmful negatives from every process, surely the results

would flow directly to the bottom line.

And they did, but not in what I thought were significant enough

numbers! What was I doing wrong? I mean the companies I worked for certainly

looked better because of my 5S events and our changeovers were being done in

record time, but the bottom line was not growing enough to suit me. Our process layouts were better, we had

manufacturing cells in place, our inventory was lower, and there was much less

waiting, but the financial results just weren’t there, at least not enough to

satisfy me. We even reduced the time it

took to purchase supplies and materials.

And not only were we not seeing positive effects on the bottom line, our

orders were still late getting to our customers. Something had to change!

In

the late 1980’s, however, something more powerful and influential came to me as

a gift….a copy of The Goal by Eli Goldratt. As I read The

Goal I began to visualize how I could apply the many lessons I had read

about. I asked myself, “Could I actually

utilize Goldratt’s teachings in the real world?” After all, this was only a fictional setting

and there really wasn’t an Alex Rogo. It

wasn’t apparent how I would use this information until the early 90’s when I

had an epiphany or maybe some would say an out-of-body experience! Goldratt’s simple, yet elegant message of

identifying, deciding how to exploit the system constraint and subordinating

everything else to the constraint changed me forever.

In

addition, to the concept of constraints, Goldratt introduced me to what he

called Throughput Accounting.

Specifically, Throughput (T), Inventory (I) and Operating Expense (OE)

took on a whole new meaning for me. It

became apparent to me that reductions in inventory typically have a one-time

impact on cash flow and after that little can be gained. It was also evident that operating expense

had a functional lower limit and once you hit it, you could actually do more

harm than good to the organization by reducing it further. Throughput, on the other hand, theoretically has

no functional upper limit! But more

importantly, throughput was only throughput if money exchanged hands with the

customer. That is, producing products for

sale is just not the same as receiving cash for them because, in reality,

it’s simply inventory.

Learning

about constraints and throughput accounting transformed me back then. I came to the realization that everything I

do in the name of improvement would give us a better return on investment if we

focused our efforts on the operation that is limiting throughput. I decided then and there that constraints are

the company’s leverage points and if I wanted to maximize our profits, then our

primary improvement efforts should be focused on the constraints. So off I went and the results were immediate

and significant. Our on-time delivery

sky rocketed! Our profits rose at an

unprecedented rate and everything was good in the world. Good until the constraint moved that is! All of a sudden my world came crashing in on

me because I hadn’t anticipated this. I

should have, but I didn’t. It wasn’t

hard to find the new constraint since there was a pile of inventory sitting in

front of it. So we just moved our

improvement efforts to the new constraint.

I learned what Goldratt meant about “breaking the constraint.”

So

here’s my message to everyone. Although

I am a huge supporter of both Lean and Six Sigma, the profits realized from

these two initiatives or even the hybrid Lean-Sigma, pale in comparison to what

can happen from an integrated Lean, Six Sigma, TOC (or as I called it in my

second book, The Ultimate Improvement Cycle (UIC)). (These days this same integration is better

known as TLS). In fact, one double blind study1 of 21 electronics

plants has confirmed that an integrated L-SS-TOC improved profits roughly 22

times that of Lean and 13 times more than Six Sigma if these were both singular

initiatives. I know what many of you are

thinking…I’m making this claim with a sample size of only one? All I can tell you is that this integration

works and it works every time!

Before

I get into how the UIC works, I want to talk about the current state of Lean,

Six Sigma and Lean-Sigma initiatives as it relates to sustainment. The Lean Enterprise Institute2

(LEI) conducts annual surveys on the subject of how well Lean implementations

are going. Considering the last three surveys (2004, 2005, and 2006), the

results do not paint a rosy picture. In fact, the LEI reported in 2004 that 36

percent of companies attempting to implement Lean were backsliding to their old

ways of working. In 2005, the percentage of companies reporting backsliding had

risen to almost 48 percent, while in 2006, the percentage was at 47 percent.

With nearly 50 percent of companies reporting backsliding, we are not looking

at a very healthy trend, especially when you consider the amount of money

invested in the initiative. Add to this what Jason Premo of the Institute of

Industrial Engineers3 reports: “A recent survey provided some

shocking results, stating that over 40 percent of Lean Manufacturing initiatives

have hit a plateau and are even backsliding, while only 5 percent of manufacturers

have truly achieved the results expected.”

And finally in 2010 research by McKinsey & Co. showed that 70% of

all changes in organizations fail!

In the case of Six Sigma

initiatives, the results have been more impressive, but not as impressive as

they could or should be. Celerant Consulting4 carried out a Six

Sigma survey in 2004, generating responses from managers across all business

sectors, and although the results of the survey were more positive than negative,

there were several problems that did surface The survey suggests that most

businesses new to Six Sigma often find that running effective projects has been

a significant challenge, with Six Sigma projects often quoted as taking four to

six months or even longer to complete. Poor

project selection is a key area where many businesses still continue to

struggle. Industry experience suggests that about 60 percent of businesses are

currently not identifying the projects that would most benefit their business.

OK, so if Lean, Six Sigma or

Lean-Sigma aren’t working well enough, then what do I recommend should replace

them. The fact is, we shouldn’t replace

them at all. They are vital to the

success of all improvement initiatives.

What is missing is the necessary focus

needed to maximize your return on your improvement investment.

What I’m about to explain is a methodology that has never failed

me. By focusing the Lean and Six Sigma

principles, tools, and techniques on the operation that is limiting throughput,

your profits will accelerate. And here,

in its most basic form, is how it works.

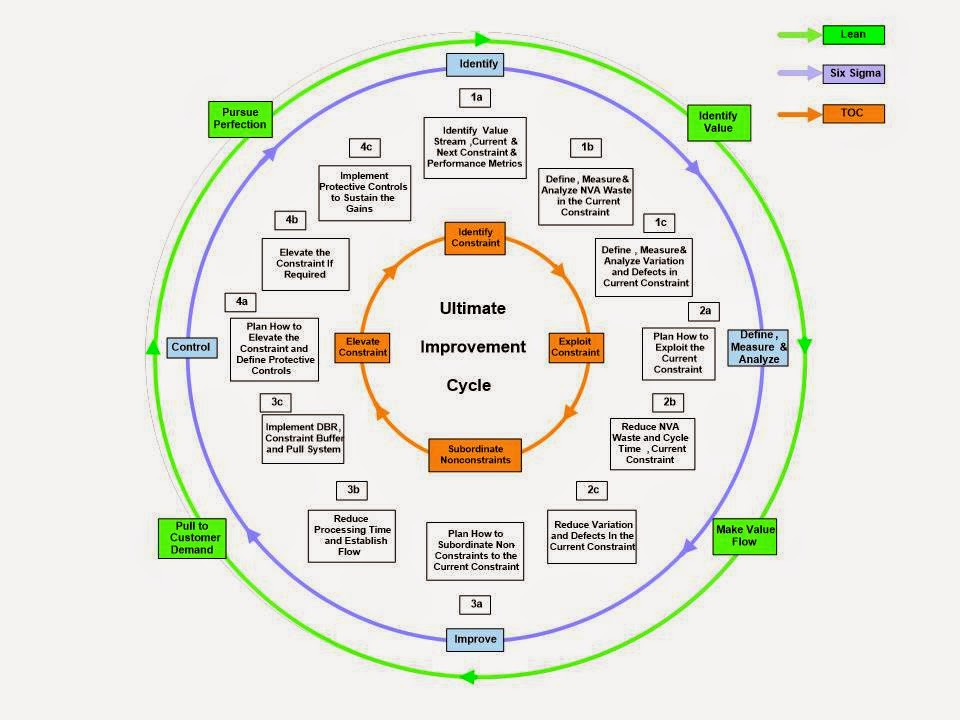

Figure

15 is a graphical representation of what I have named the Ultimate

Improvement Cycle. What you see are

three concentric circles representing three different cycles of

improvement. The inner or core cycle

represents the Theory of Constraints (TOC) process of on-going improvement6. TOC provides the necessary focus that is

missing from Lean and Six Sigma improvement initiatives. Based upon my experience and results, the key

to successful improvement initiatives is focusing your improvement efforts on

the right area, the system constraint.

Remember, the constraint dictates your throughput rate which ties

directly to bottom-line improvement.

Throughput in this context is revenue minus totally variable costs

(TVC). TVC’s includes things like the

cost of raw materials, sales commissions, shipping costs, etc…..anything that

varies with the sale of a single unit of product.

The

second circle represents the Six Sigma roadmap popularized by at least two

authors7,8. Here you will

recognize the now famous D-M-A-I-C roadmap associated with Six Sigma. The outer circle depicts the Lean improvement

cycle popularized by Womack, Jones9 and others. Both Six Sigma and Lean are absolutely

necessary for my methodology to work…..the only difference being where and when

to apply them.

Figure

25 summarizes the tools and actions needed to effectuate the

improvement in the constraint and a general idea of when to use them. Keep in mind that all processes are not the

same, so the type of tool or action required and the usage order could be

different depending upon the scenario.

This is clearly situation dependent.

I won’t go through each step in Figures 1 and 2 because they are

self-explanatory. Let’s look at a brief

case study which I did not cover in my book.

This

case study involves a company that had been

manufacturing truck bodies for the transportation industry since 1958 and had

been one of the recognized industry leaders.

The company had a staff of 17 full time Engineers and Engineering

performance was measured by the number of hours of backlog waiting to pass

through Engineering, which seemed odd to me that such a negative performance

metric was being used. I had been hired

in as the VP of Quality and Continuous Improvement because the company was

losing market share as well as delivery dates being missed. In addition, morale within Engineering was

apparently at an all time low. Upon

arriving at this company I was informed that I was also to have responsibility

for Engineering. Because of the poor

performance in Engineering, the company had fired their VP of Engineering and I

was the “lucky” recipient of this group.

Apparently the backlog of quotes had risen from their normal 300 hours

to approximately 1400 hours just in the previous 2 months.

My first step was to create a high-level P-Map

and a VSM to better understand what was happening. I was in search of the constraint or that

part of the process that was limiting throughput. It was clear immediately that the constraint

was the order entry system in that the process to receive a request for a quote

and deliver it back to the customers was consuming 40 days! And since it only took 2 weeks to produce and

mount the truck body, it was clear to me why market share was declining. I then created a lower level P-Map of the

quoting process to better understand what was consuming so much time.

My

next step was to develop a run chart to get some history of what was happening

within this process. Figure 3 represents

the number of backlog hours from February 1999 through April 2000. The data confused me because I first observed

a steady decline in backlog hours beginning in May of 1999 through October 1999

and then a linear increase from November 1999 through April of 2000. My investigation revealed that the decline

was associated with mandatory Engineering overtime and the ascent occurred when

the overtime was canceled. The

Engineering VP hadn’t defined and solved the problem, he had just treated the

symptoms with overtime.

My

next step was to create another run chart going back further in time. If I was going to solve this problem, I

needed to find out when this problem actually started. Figure 4 is the second run chart I created

and it was clear that this backlog problem was a relatively recent change, so

the key to solving it was to determine what had changed.

Figure 3

Figure 3

In

fact, somewhere around January of 1999 the incumbent VP of Engineering had

decided to move on to another position outside the company. His replacement apparently didn’t like the

way the Engineering Group was arranged.

The company produced three basic types of truck bodies and historically

had three different groups of engineers to support each type. These groups were staffed based upon the

ratio of each type of truck body ordered and produced. Between June of 1996 and December 1998 the

company had maintained a very stable level of backlog hours. The new VP of Engineering consolidated the

three groups into a single group and almost immediately the backlog grew

exponentially. The company fired him in

May 1999 and hired the new VP that used overtime to bring the backlog hours

down. Part of the problem was the performance

metric in place which caused abnormal and unacceptable behaviors.

For me,

the fix was clear. Return to the

previous Engineering configuration, identify the system constraint, focus on it

and drive out waste and variation, to drive the backlog hours lower. The results were swift and amazing in that

the backlog decreased from 1200 hours

to 131 hours in 5 weeks and has remained within an acceptable maintenance level

ever since. In fact, because we also

eliminated much of the waste within this process the time required to process

orders through Engineering decreased from 40 days to an astounding 48 hours! Figure 5 represents the final results of our

efforts. Not only had the amount of

backlog hours decreased to levels never seen before (from a historical average

of 300 hours to less than 150 hours), the number of quotes completed were at

all-time highs for the company.

The

key to this success was to first identify the operation that was constraining

throughput (the system constraint), second, decide how to exploit the

constraint by applying various Lean and Six Sigma tools to the constraint,

third, subordinate everything else to the constraint and then if need be, break

the constraint by spending money. Thanks

to Lean and Six Sigma, we did not have to spend any money. And the good news is, Engineering overtime

was virtually eliminated while the market share rose to unprecedented levels!

References

- Reza M. Pirasteh, PH.D., and Kimberly S. Farah, PH.D. - The Top Elements of TOC, Lean, and Six Sigma (TLS) Make Beautiful Music Together, APICS Magazine article, May 2006.

- Lean Enterprise Institute, 2004 and 2005 Surveys on Lean Manufacturing.

- Premo, Jason P., Please Help! My Lean Is Broken, Institute of Industrial Engineers.

- Survey by Celerant Consulting, December 2004.

- Reprinted with permission from The Ultimate Improvement Cycle – Maximizing Profits Through the Integration of Lean, Six Sigma, and the Theory of Constraints – CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL, 2009

- Goldratt, Eliyahu M., The Goal (Great Barrington, MA: North River Press, 1986)

- Harry, Mikel, and Richard Schroeder, Six Sigma: The Breakthrough Management Strategy Revolutionizing the World’s Top Corporations (New York: Doubleday,2000).

- Pande, Peter S., Robert P. Newman, and Roland R. Cavanaugh, The Six Sigma Way—How GE, Motorola, and Other Top Companies Are Honing Their Performance (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000).

- Womack, James P., and Daniel T. Jones, Lean Thinking—Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation (New York: Free Press, 2003).

Bob Sproull

No comments:

Post a Comment